A few months back, I was watching Framlingham Town play Swaffham in the Vase. It was awful, so bad that there was an audible groan from fans and players alike when the ref blew the whistle for ninety minutes and announced we would have extra time. But I loved it. Standing there in the September sun, watching the half-arsed efforts of the butchers, bakers and candlestick makers of these two Suffolk towns, I reached enlightenment. Because there was a certain magic to the occasion, and one that would be ruined should any of these hapless footballers actually achieve what they were presumably hoping to achieve, and score a goal. So much of watching football is about the shared experience, even if you don’t say a word to your fellows, and the collective dismay of the small crowd was the thing that was bringing us together. Which is lucky, because truly great games are few and far between – the truly magical even more so.

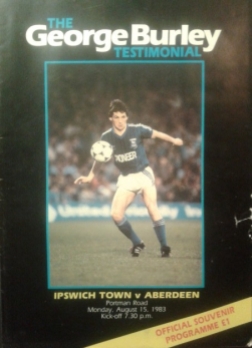

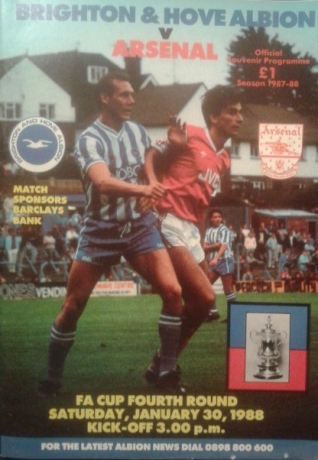

As a boy, every game I went to made my spine tingle – it was all a thrill, and magical, in the way that life is when things are experienced for the first time. England against Spain in 1981, Charlton hosting Newcastle a year or so later, Ipswich and Aberdeen in George Burley’s testimonial on 1983 – I can still remember how these games made me feel. In fact, my memory of those sensations – the noise, the smell, the occasion – is stronger than my memories of the games themselves. Standing at the Clock End in the snow watching Arsenal outplay QPR in 85, Ipswich’s almighty battle with Oxford to stay up in the First Division in 1986 and Arsenal’s visit to Brighton, then two divisions below, in the fourth round of the cup in 1988 – forget madeleines, I just need a whiff of a Wagon Wheel and I am transported.

And to be standing just a few yards away from the players! Kevin Keegan, with Brooking and Hoddle playing against Gordillo and Camacho, Arconada in goal. The unlikely Division 2 meeting of two former European Players of the Year at the Valley, except that Keegan was injured and didn’t play – Simonsen did however, and was wonderful. Strachan, Charlie Nicholas, Terry Butcher, Johnny Wark, Aldridge, Perryman, Perry Groves! The list goes on. I’d seen them on the telly and in my sticker books, and here they were – for real.

I don’t think that I can claim that any of these early encounters can be classified as truly great games, although the last minute win for Ipswich over Oxford was certainly an epic – Butcher at his bloodied best, head split and stitched up before somehow forcing the win that we all thought had kept the Town up. It hadn’t, but we didn’t know that at the time. They were magical to me, of course, and remain so but I am not sure that these games were magical, in the collective sense – when the whole crowd understands that they have shared in something special.

The first game I went to that falls into the latter category wasn’t even a good game of football – it was a one each draw between Scotland and Norway, but it was magical alright. It was my only visit to the old Hampden, and on a mild but damp evening I saw Scotland qualify for the World Cup. It was November 1989 and the World was watching in amazement as the Berlin Wall came down. I, however, barely noticed it – I was too excited about seeing Scotland play. The game was mediocre, and a late Norwegian goal made for an anxious last five minutes, but Scotland held out and, standing out on the big open terrace (the Celtic end), I had my only experience of the Hampden Roar. It was unforgettable. A few years later the place had been rebuilt and the atmosphere killed. Scotland have only qualified for one World Cup since. Coincidence?

There have been other great games and wonderful occasions. Scottish Cup Finals, a childhood dream coming true to see Ipswich winning at Wembley, another schoolboy fantasy realised when Scotland equalised against Brazil in the opening game of the 1998 World Cup. But they all play second fiddle to what was, without doubt, the greatest game of all time. I know, because I was there. It took place in Aberdeen, under the floodlights of a jam packed Pittodrie. Bouyed by a terrific first leg result, one all in Germany, twenty two thousand turned out on a bitter cold and foggy night to see the Scottish under 21s play for a place in the semis of the European Championships. The ground was buzzing in anticipation – the atmosphere enhanced by the lights sparkling through the fog. Two first half goals from Germany applied a dose of realism and quietened things down, but a goal just before the break stoked it up again. And then, in the 53rd minute, Heiko Herrlich scored and Pittodrie was silenced.

Germany led 4-2 on aggregate, they had three away goals and Scotland needed three to stay in the tournament. The tie was, to all intents and purposes, dead and buried, or should have been. But Herrlich, instead of running to his teammates, decided to celebrate by puffing out his chest and walking, matador style, down the length of the South Stand. It was magnificent stuff, an act of supreme arrogance and all the better for it. It was, however, unwise – the response of the home crowd was extraordinary.

It began with catcalls and laughter, shouts and abuse, the odd groan. But it grew into something else. A low rumble of discontent became something determined – a voiced rolling up of sleeves. Pittodrie began to growl. The initial indignation had morphed into an intense sense of collective willpower – we were going to do something more than support. We were going to will Scotland to victory, and we did just that.

The rest of the game is a blur – with twenty minutes left, Gerry Creaney scored. The noise continued to build – ten minutes later Paul Lambert added another and Scotland just needed the one goal. I have never experienced anything like it – the stadium fizzed and crackled as we roared Scotland home. With two minutes left the ball reached Alex Rae and, as I remember it (and this is a hazy memory at best – I have never seen any film of the goal), he struck the ball straight and true from the corner of the penalty area. Scotland had made the impossible possible. No, we had made the impossible possible – all of us. The place went mental. I found myself hugging strangers, drunk on the euphoria. We could not believe what we were seeing, what we had seen.

I left the ground in something of a daze, excited chatter all around, headed down the Merkland Road and along the cobbled streets to the Machar Bar in Old Aberdeen. I had gone to the game alone and left alone – the intense camaraderie of the previous two hours was over. I wanted to tell people about it but knew that I didn’t have the words to describe what I had just seen and experienced. It didn’t matter – I had felt the magic. I had just seen the greatest game of them all.